I celebrated 2022 with a breast cancer diagnosis looming like little black clouds (happy f**king new year).

Fortunately, the radiologist caught cancer during my annual mammogram. Later, an MRI showed that cancer hadn’t spread to the lymph nodes or outside my breast.

“You still need a surgeon to take out the area,” said the doctor. I took his call on a cold night in January just as I was about to play tennis. “I didn’t see any cancer from the MRI,” he continued. “The biopsy might have taken care of it. There’s a confidence that the mass is not bigger than we thought.”

That was excellent news.

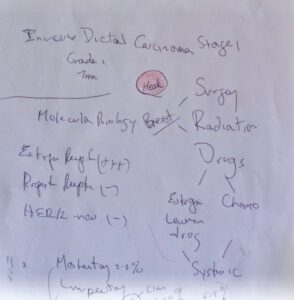

Following the advice of my radiologist, I met with a top breast cancer surgeon. He was informative, kind, and patiently answered all of my questions. He even drew a diagram.

I decided on a lumpectomy (where the surgeon removes the tumor and some normal breast tissue to get good margins). I also needed a sentinel node biopsy (removing two lymph nodes in my armpit to ensure cancer hadn’t spread to other areas). The surgeon recommended radiation (to kill tumor cells) and hormone therapy (to block estrogen from stimulating any cancer cell growth). I also spoke with a genetics counselor about my family history and decided to have genetic testing.

I had a plan: Get rid of cancer, kill any chance that it will spread or come back anywhere else, and live an active, healthy, and happy life. I was on a high. I would be out of work for two to three weeks and back to playing tennis in no time.

I was wrong.

Three factors contribute to breast cancer – aging, environment, and genetics. The majority of breast cancers are not genetically based. Only 5 to 10 percent of breast cancer is thought to be hereditary. However, not everyone with a gene mutation gets breast cancer, but they have a higher risk. Since Angelina Jolie shared her story in the NY Times in 2013, genetic cancer panels have broadened beyond the terrible BRCA1 and BRCA2 gene mutations. Research shows there are more gene mutations with clinical implications beyond breast cancer.

The results of my genetic testing showed that I have an ATM gene mutation. Ataxia-Telangiesctasia Mutated (ATM) is a repair gene that can be damaged by toxic chemicals or radiation. I already had cancer in one breast, making it more likely to get cancer in the other breast. The ATM gene mutation gave me a 52 percent chance of developing another breast cancer and increased my risk of pancreatic and ovarian cancer during my lifetime.

I didn’t like those odds.

At the beginning of my diagnosis, I admitted to searching Google for answers, which led this curious rabbit down a deep, dark hole. One search bled into another. Suddenly, I found myself learning about everything and anything. Clicking on words and phrases in the dark hours became too much. I had to claw and scrape my way out of the great oracle’s grasp.

One afternoon in January, I received a goodie bag from my wonderful friends at the Breast Cancer Coalition of Rochester (BCCR). Among all kinds of thoughtful items was the best gift: Dr. Susan Love’s Breast Book (sixth edition) – the bible for women with breast cancer. I dug in with gusto, marking pages with book darts and yellow highlighter. Dr. Love’s witty and no-nonsense approach to explaining the breast was oddly comforting.

One afternoon in January, I received a goodie bag from my wonderful friends at the Breast Cancer Coalition of Rochester (BCCR). Among all kinds of thoughtful items was the best gift: Dr. Susan Love’s Breast Book (sixth edition) – the bible for women with breast cancer. I dug in with gusto, marking pages with book darts and yellow highlighter. Dr. Love’s witty and no-nonsense approach to explaining the breast was oddly comforting.

We are born with “a nipple and lots of potential …”

Cancer needs both “a mutation and the right environment to grow.”

A gene mutation caused my breast cancer. This mutation increases the likelihood of getting another cancer during my life regardless of how well I take care of myself. All cancer is probably caused by a mixture of genes altered by carcinogens and stimulated by an environment that makes it easy to grow and spread. Now that this bad actor is awakened, where will it go next? When will it occur? Is it a question of when and not if? How often do I want my life interrupted by cancer and treating cancer? Should I change my treatment plan? Little black clouds obscured my vision.

I got a second opinion.

Having this gene mutation was one more piece of data to consider. I asked questions and listened to the doctors’ responses.

ATM is tough. We don’t downplay it.

The gene mutation is active now that there is breast cancer.

Bilateral mastectomy lowers risk by 95 percent.

Could do less surgery and watch closely.

Radiation may interfere with reconstruction in the future.

Patients with ATM chose bilateral mastectomy.

Patients with ATM who opted for lumpectomy were seen for a second cancer within 5 years.

There is no crystal ball.

It is not an overreaction to have a bilateral mastectomy.

Making decisions, asking questions, and talking about my feelings proved exhausting. I was swimming in a sea of emotions. There comes a time to stop. Stop researching. Stop reading. Stop talking. I needed to trust my gut.

This decision was tough, but it was my call. I chose a bilateral (double) mastectomy. With this choice, I learned that my relationship would not only be with my breast surgeon (surgical oncologist) but also with a reconstruction surgeon (plastic surgeon). I would be in their care for months following surgery. I met with two plastic surgeons skilled in breast cancer reconstruction. The first surgeon I met didn’t give me the warm fuzzies. After meeting with the second surgeon, I knew I had someone in my corner whom I could trust and feel 100 percent comfortable with as I made more choices. I wanted implants, not tissue reconstruction. And I decided on silicone over the pectoral muscle. I felt a sense of achievement.

Brave is controversial.

I have a blue, heart-shaped stone on my desk etched with the words Brave. It reminds me of the choices I’ve made in my life. Some choices I’ve shared with the world. Others I kept private. I had a new plan – one I didn’t see coming initially. I felt more optimistic about the future, although I had yet to walk through the valley of pain. Even the best-laid plans sometimes go awry. Little black clouds happen. I’m reminded of what a wise friend said to me:

There will be many challenges along the way. You can’t control everything, but you will get through it.

Searching for equanimity

Searching for equanimity